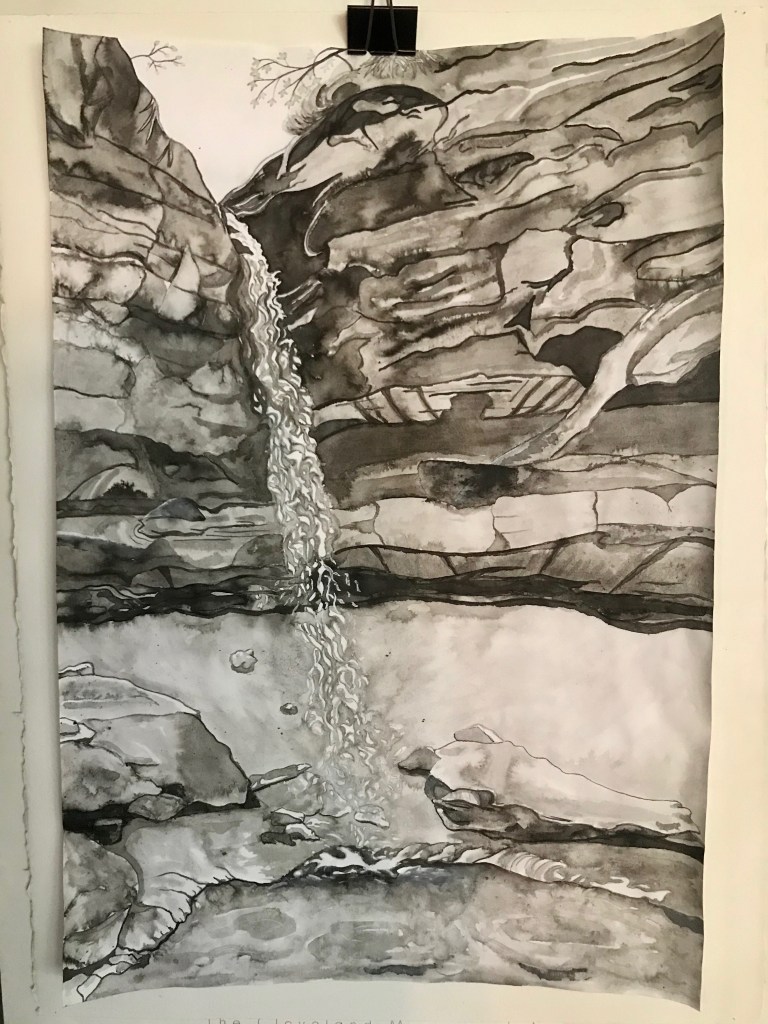

I’ve had the good fortune to publish three books, and each time was able to use an image for the cover created by a local artist’s work (I’ll get back to this). With Letters from the Karst, Teresa Christmas, though she was in the middle of her fall art classes, agreed. Her drawing of Shanty Hollow, the local woodsy trail that ends at a waterfall, beautifully captures karst country. Here it is:

What I didn’t know is that Teresa has a direct connection to Floyd Collins, the famous caver and fortune hunter who was trapped in Sand Cave up the road a few miles from Bowling Green. The spectacle that resulted with attempts to rescue him captured the attention of the entire country. This is described brilliantly in Robert K. Murray and Roger W. Brucker’s Trapped: The Story of the Struggle to Rescue Floyd Collins from a Kentucky Cave in 1925. It’s a page-turner. Everything for a first-rate melodrama came together in Floyd’s story: bravery, tragedy, massive media coverage, schemers, betrayers, technology, Kentucky culture and history, and medical rescue (failure).

I had to make a connection to Floyd’s story in a novel about the karst system, right? . . . hence the fictional birth of the Collins family, related somewhat distantly to Floyd, through the current-day grandmother’s father, who was Floyd’s cousin.

So I was pleasantly surprised when Teresa told me what she discloses in her artist’s statement:

I am a Kentuckian. My ancestors, for five generations, or more, have lived their lives in the remote hollows and the rocky slopes of south central Kentucky where they are buried in graveyards and homesteads lost to memory. Floyd Collins is my grandmother’s first cousin.

This is almost exactly the lineage I invented. Meant to be?

Also in her artist’s statement she talks about her choices for the drawing, beautifully seeing exactly what I was trying to do in the writing:

My choices for content, media and design were—I realized almost after the fact—inspired by the complicated and nuanced emotional responses Jane managed to evoke in me as I navigated her web of interconnected tales—not a roller coaster ride, exactly, but a winding trail, for sure—one that leads through bright sunshine and dark shadow.

Black ink wash seemed the perfect way to explore those gradations of light and dark, and I have always been drawn to traditional Asian black ink art, in part because it can capture flowing water in ways that other media cannot.

I admire what artists can covey, taking what’s inside and transcribing it for others to see. My son has this ability, and I was very happy that he agreed to do the cover for my second book, a memoir, The Tree You Come Home To:

He was sensitive in his choice of colors and blurriness (my word for it), due to the content, which tells the story of his youngest brother, who was killed in 2009, and my own approximately four-year journey to healing. There’s a sense of light coming through, sunrise maybe, and the purple evokes the emotional depths that we had to travel. I love the fence emerging on the left and disappearing into the mists behind the tree.

And that brings me to the artist I prevailed upon for my first book, Yvonne Petkus, professor of art at WKU. Her painting, Braced, is wonderful for Seeking the Other Side, my collection of poems. Doesn’t this woman evoke the embodied yet coming apart aspect of seeking the deeper meanings of life? Or, is she coming back together after being partly dis-embodied? Or, is this what happens over and over again in life as we journey away from and (hopefully) return to our full selves?

In an exhibition catalog, Searching, another local artist and WKU professor, Kristina Arnold, describes Petkus’s work, noting how it “unashamedly confronts the physical and psychological effects of violence and the collective residue accrued both individually and as a society through repeated trauma.” Yvonne described to me the repeated imagery of the woman coming into and going out of a visible sphere as evoking a process, about the becoming of self as many acts of courage or questing. Perfect.