This is the title story, told by the middle daughter, Cecily, along with a series of letter. This first chapter and the last one, “Extremophiles,” narrated by her mother, provide the bookends for the Collins family story. I won’t divulge anything that belongs to Cecily, so this will touch on other things.

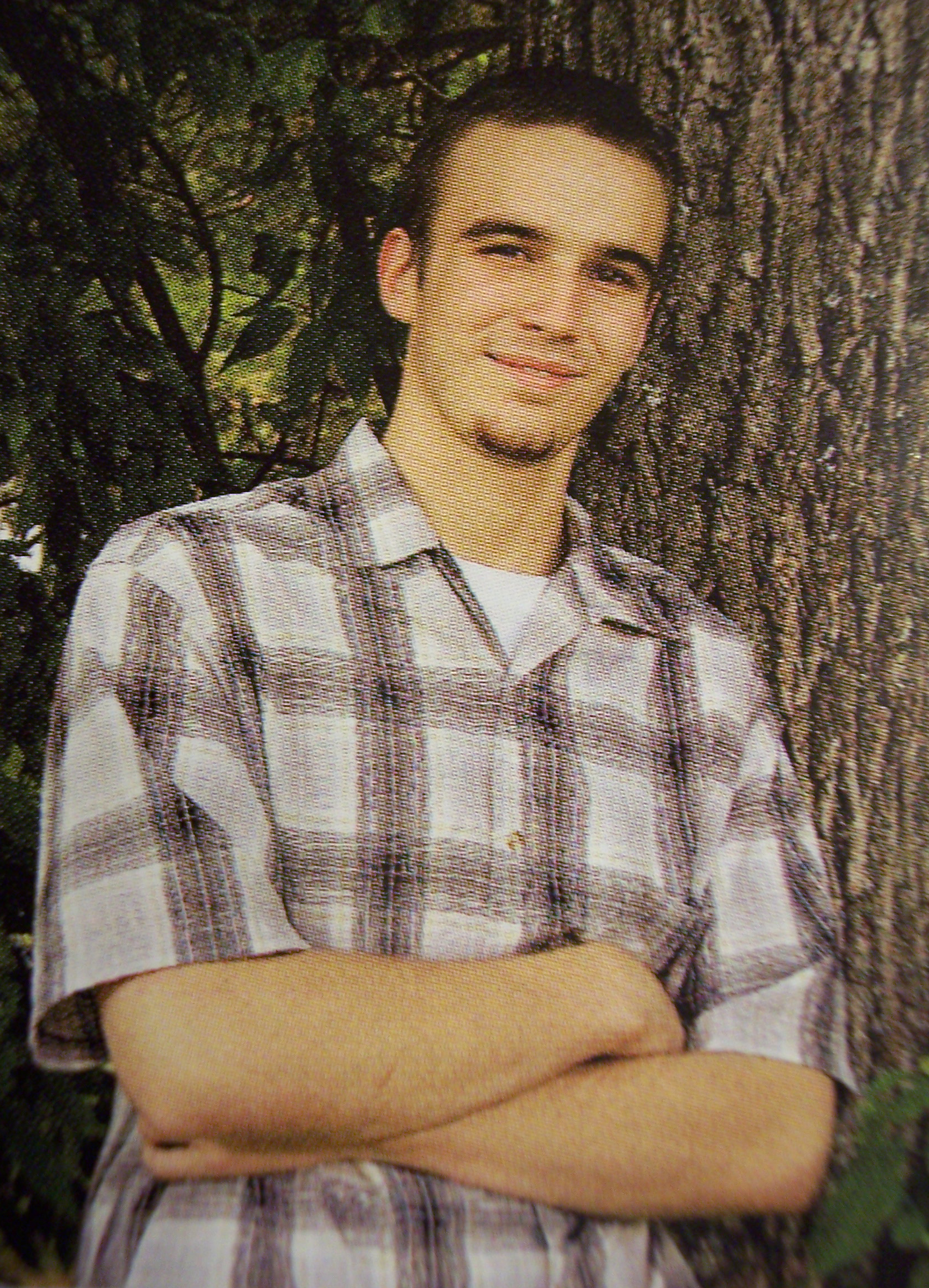

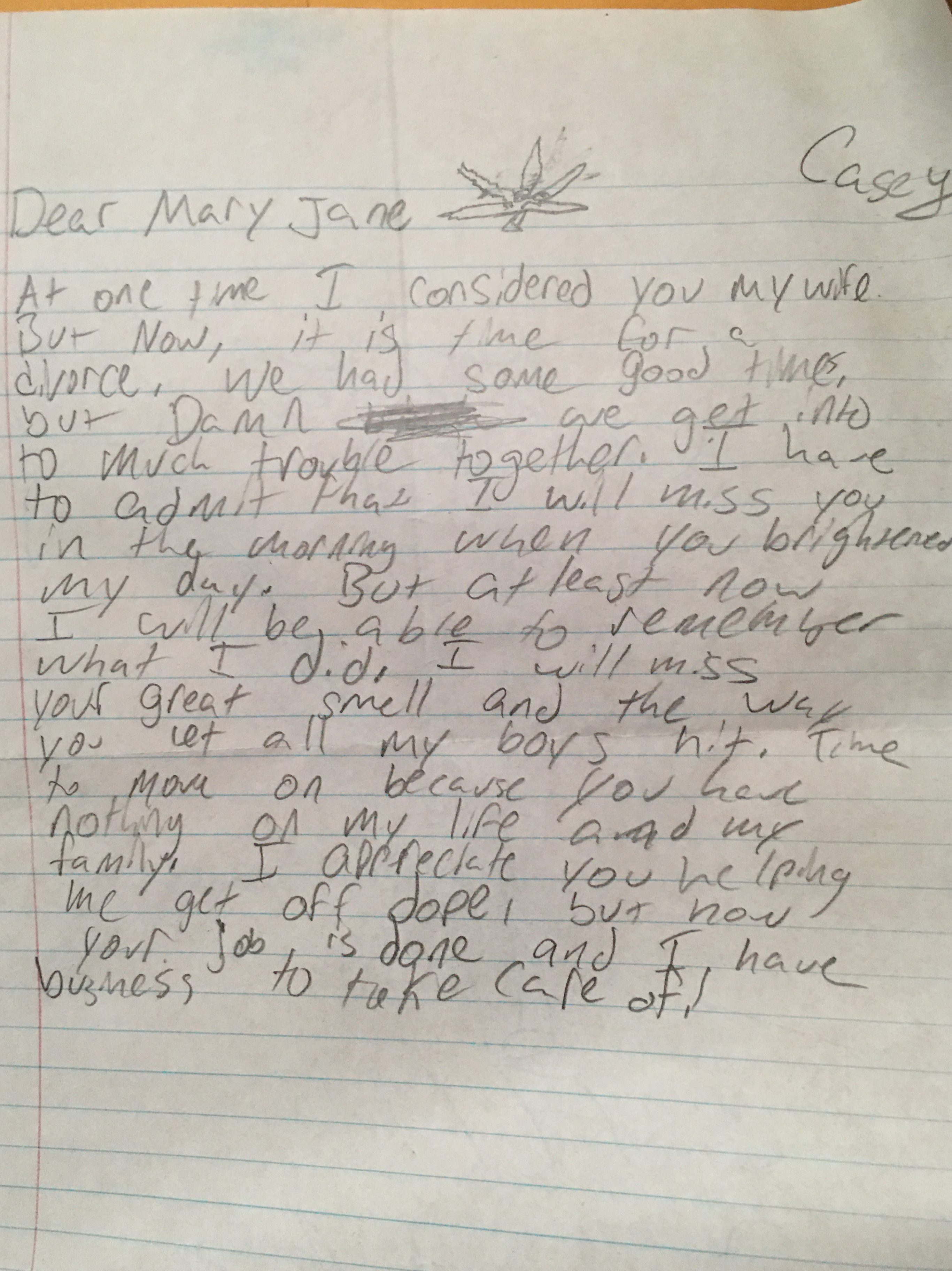

Cecily has suffered from pretty severe substance abuse; the probable cause is divulged in her story. I have some experience with the intractability of addictive behavior, its seductions and high costs. My youngest son struggled throughout his teen years, spending most of his days in various institutions—special schools, incarcerations, treatment centers. Even when he was at home, he was on yard restriction and we went to weekly treatment and therapy sessions. When he was killed at age twenty, the autopsy declared his toxicology negative. His painful journey ended as he was making a turn-around, perhaps the one that would have set him on a better path. I am sure that Casey was in my thoughts when I wrote from Cecily’s perspective or about her in another chapter, which belongs to a former boyfriend, Derek (but more on him later). I tell Casey’s story along with my own and my family’s journey to healing in The Tree You Come Home To, which you can read about, under “Memoir.” (Here is a picture of Casey with his counselor Mr. Wright after he completed his time at Care Academy, about two hours from home, with his symbolic monkey around his neck.)

Cecily is the second of three girls born to Meredith and David. Her older sister, Diana, like so many oldest children, feels that she must bear the responsibility for her siblings’ well being. Because the younger sister, Molly, was born on the same day as Cecily, Cecily has always thought of Molly as belonging to her. In Letters from the Karst, this tight-knit group of siblings come to the fore and then recede as the other characters take their turns.

I think I was drawn to writing about siblings because I was an only child—at least I was raised as an only child, my three brothers and sister being raised by our father and their stepmother two states away. As a child I made friends with girls from big families (not coincidentally). One in particular, Barbara Dodson, shared the same birthday, which made us instant best friends. Her large family lived a block away and I remember being there whenever I could. I loved eating dinner with them at the end of a day of play. It was always hotdogs or canned spaghetti and I thought their meals were divine. I remember her uncle peering into the bottom of the TV screen to try to see into the cleavage of some actress. Male humor was completely foreign to me, living as I did with my mom, just the two of us. So writing Diana, Cecily, and Molly into being seemed to bring someone I already knew to life.

To order Letters of the Karst, request it from your local library or order from amazon, here.